Coordination of social security benefits and the services provided as part of them as well as boosting incentives for work have been some of the key goals in the preparation of the social security reform. For several parliamentary terms, digitalisation and better focus on client needs have been two of the instruments used to make public service systems and permit processes more effective. The audits of a number of separate systems show that improvements have been achieved but there is still work to do.

General housing allowance has become an important form of support for households with low earned income

To overhaul the housing allowance scheme, the parliamentary committee preparing the social security reform proposed in its interim report on 16 March 2023 that an extensive study should be carried out to find answers to the following questions:

How should housing allowance be allocated to different beneficiary households (low-income earners, students and diverse families with children) by municipality class or commuting area?

Has the existing earned-income deduction (earnings disregard) boosted the income, wellbeing or employment of housing allowance recipients?

How would an increase in the maximum housing costs providing eligibility for housing allowance impact the number of social assistance recipients?

What have been the impacts of the abolition of means testing?

The audit conducted by the National Audit Office provides partial answers to these questions.1 In its audit of general housing allowance, the National Audit Office examined the effectiveness of the earned-income deduction as an incentive to part-time work and as an instrument to reduce structural unemployment. Earned-income deduction, which was introduced in 2015, means that when the amount of housing allowance is determined, EUR 300 is deducted each month from the earned income of each adult household member. The auditors also examined the incentive effects of the earned-income deduction and the compatibility of housing allowance with study grant and social assistance.

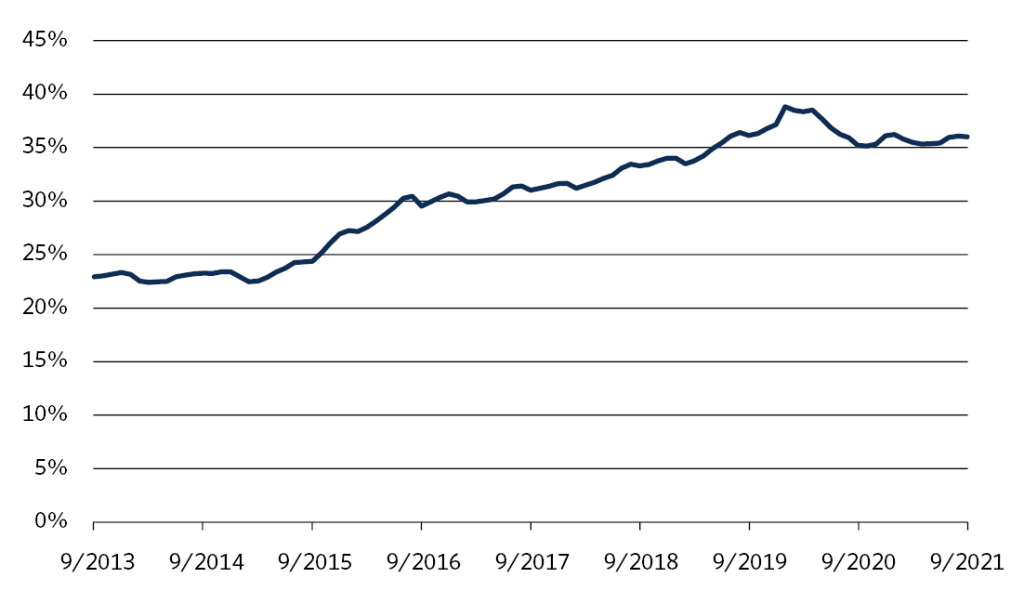

Based on the audit, since the introduction of the earned-income deduction, general housing allowance has become an important form of support, especially for households with low earned income.1 The deduction boosts the disposable income of benefit recipients who are at work and thus it also reduces the need for social assistance. This was also the aim when the earnings disregard of general housing allowance and unemployment security was introduced. The introduction of the earned-income deduction of housing allowance increased the amount of housing allowance granted to earned-income households and the number of households eligible for general housing allowance. The proportion of earned-income households of general housing allowance recipients increased from 24 to 39 per cent between 2015 and 2019 (Figure 1). Students are not included in the figures.1

Even though the earned-income deduction of general housing allowance encourages benefit recipients to work part-time, social assistance is also extensively used to cover housing costs

Incentive traps include situations where income from work does not significantly boost disposable income or where combining earned income and benefit income is particularly difficult for an individual and may cause interruptions to income.

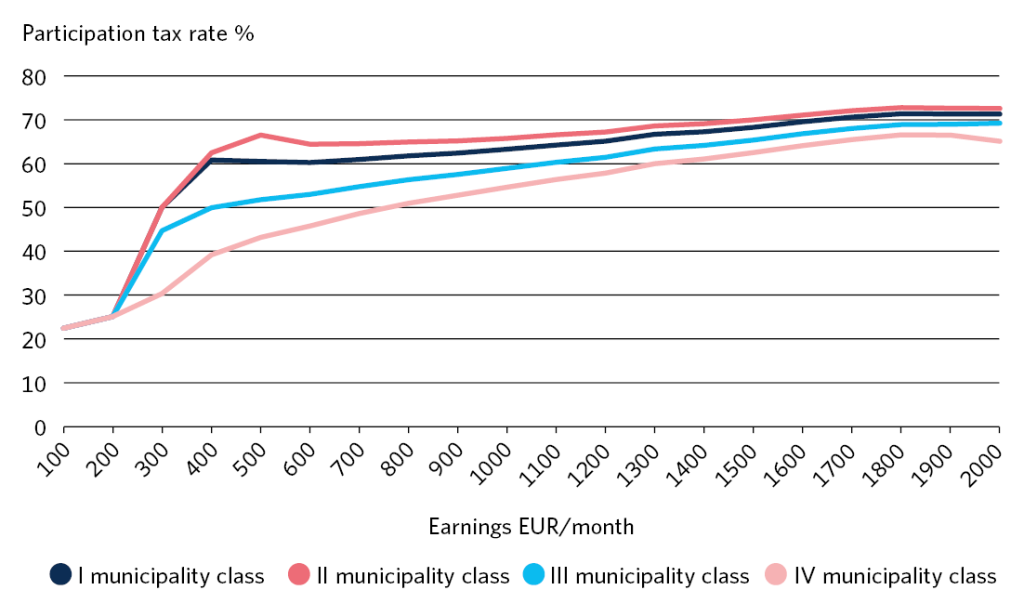

Based on the calculations made in the audit using the SISU microsimulation model, part-time work does not become an incentive trap for typical households receiving general housing allowance.1 Earned-income deduction makes part-time work more attractive to single-parent families living in the Helsinki region and receiving labour market subsidy. Likewise, one-person households receiving labour market subsidy do not face any employment-related incentive traps when their monthly income is between EUR 100 and 2,000 (see Figure 2). Without the earned-income deduction, the participation tax rate of unemployed one-person households in the Helsinki region would be nearly 80 per cent, which means that it would already be close to the theoretical unemployment trap with monthly income of EUR 600.1

Based on the calculations produced by the National Audit Office, earned-income deduction has made part-time work the most economically attractive option for higher education students receiving general housing allowance and study grants as their participation tax rate remains below 50 per cent throughout the country.1 Despite these economic incentives for work, students should be able to assess both the impacts of their own income on study grants and the impacts of the income of adult members of their households on general housing allowance. However, the problem for students is that the general housing allowance is determined on the basis of the calculated average income of the household for the coming year whereas the study grant is determined on the basis of the student’s personal income.1

Housing allowance recipients living outside the Helsinki region (especially those with low earned income) have stronger incentives for employment than households in the Helsinki region. This is because the housing costs are lower outside the Helsinki region, which means that unemployment security and general housing allowance can better meet the housing costs.

However, a significant proportion of the housing costs is also covered with social assistance: at the moment, basic social assistance recipients use nearly 50 per cent of the assistance to pay housing costs. Using social assistance weakens the economic incentives for work, and strict means-testing makes participation in work more bureaucratic. If the conditions for receiving housing allowance are tightened, recipients must cover a higher proportion of their housing expenditure with social assistance. The high cost of housing thus makes it more difficult to reduce the need for long-term social assistance, one of the objectives of the social security reform.1

Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (ARA) helps to ensure social housing construction

Affordable state-subsidised ARA housing construction supplements market-based supply of housing and mitigates the impacts of business cycles. Agreements on land use, housing and transport (MAL agreements) between central government and large cities have proved an effective instrument to implement a long-term housing policy. The Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (ARA), a party to the MAL agreements, provides grants, subsidies and guarantees for affordable housing construction. ARA also steers and supervises the use of the ARA housing stock.

Based on the audit of ARA’s operations, most of the objectives of the MAL agreements and the performance targets set for ARA have been achieved but the financial instruments used by ARA do not fully meet the needs of developers and providers of funding.2 Demand for ARA housing is maintained by population growth, affordable rents and low turnover of the dwellings. Especially in large cities, it is difficult to meet the demand for social housing construction with non-subsidised housing construction and the prevailing rental levels. In many cities, there is also a shortage of plots suitable for affordable housing construction. However, with certain exceptions, ARA does not grant interest-subsidy loans to medium-sized regional centres with between 50,000 and 100,000 inhabitants where population is not growing. Rental housing corporations in such cities have limited opportunities to finance new construction and renovation projects.2

Recommendations of the National Audit Office for preparing the social security reform and boosting social housing construction

It should be decided to what extent the subsistence of households with low earned income should be supported with general housing allowance and to what extent with other benefits.1

Solutions should be developed to reduce the need to cover housing costs with social assistance, a benefit intended as last-resort and temporary assistance.1

Government proposals should include assessments of the objectives of the reforms, their impacts on central government finances, other impacts and of alternative ways to implement them.1

To boost social housing construction, the need for and feasibility of financing rental housing corporations in medium-sized regional centres with interest-subsidy loans granted by ARA should be examined.2

The process of assigning beneficiaries of international protection to municipalities and the monitoring of the assignment process have improved, and persons in need of temporary protection are eligible for a municipality of residence

In order to streamline the asylum process, assignment of beneficiaries of international protection to municipalities and their transfer from reception centres to municipalities have been developed in a target-oriented manner, and the processes were comprehensively assessed in connection with the reform of the Act on the Promotion of Immigrant Integration (936/2022, HE 208/2022 vp). This was also the conclusion made in the follow-up on the audit discussing the same topic (2/2018). Development focus has been on the reception process, imputed compensations, assignment of quota refugees to municipalities and improving access to information. Monitoring of and reporting on the assignment process have also been improved in recent years. However, it could not be unequivocally concluded in the follow-up that existing information systems sufficiently support sharing of information between actors.3

As part of the same follow-up, it was also examined how Finland has implemented the European Union directive on temporary protection, which entered into force on 4 March 2022. The directive is intended for people fleeing the war in Ukraine. The temporary protection process is simpler and quicker than the normal asylum procedure. One step in the implementation of the directive was the preparation of the amendments to the Act on the Promotion of Immigrant Integration and the Reception Act that entered into force on 1 March 2023. Under these amendments, central government pays municipalities and wellbeing services counties compensation for providing services to beneficiaries of temporary protection who have been granted a municipality of residence. Beneficiaries of temporary protection may apply for a municipality of residence after they have lived in Finland for one year. Preparation of the legislative amendments was speeded up by a report on the right of the beneficiaries of temporary protection to a municipality of residence (VN/6332/2022), which was completed in spring 2022. In the municipal placement targets of the Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY Centres) for 2023, consideration has also been given to the beneficiaries of temporary protection.3 The Ministry of the Environment also prepared a draft government proposal in spring 2023 proposing that the beneficiaries of temporary protection could be assigned to state-subsidised dwellings regardless of the duration of the residence permit granted. The purpose of the proposal is to facilitate the arrangement of housing in municipalities for persons that have fled the war in Ukraine.

In the view of the National Audit Office, the functioning of the system for assigning beneficiaries of international protection to municipalities can only be reliably assessed after the entry into force of the new Act on the Promotion of Immigrant Integration in 2025.

Permit processes for work-based immigration have been speeded up but the family reunification process and the granting of professional practice rights in health and social services remain slow

Since 2003, promoting work-based immigration has been mentioned in the Government Programmes as an instrument to strengthen the Finnish economy and ease the situation in sectors facing from labour shortages. The National Audit Office of Finland has examined the administrative processes of the service system for work-based immigration.4 Based on the audit, the work permit processes have been systematically improved after the administration of work-based immigration was transferred to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment in 2020. The permit processes have been speeded up by such factors as automation and the appointment of additional permit officials. The two-week target time for the processing of residence permit applications of specialists, start-up entrepreneurs and their family members was achieved in 2021. The fast track service and D visa were introduced for these persons in June 2022.4

The D visa was expected to facilitate the fast track process so that specialists, start-up entrepreneurs and their family members can travel to Finland as soon as they have been granted residence permits. According to an official estimate, the permit process would be shortened by between one and two weeks, and this can only be achieved if the applications for a long-term visa and the residence permit are submitted simultaneously in the e-service. According to the audit findings, the fast track procedure and D visa have not, in the early stages of the new arrangement, boosted work-based immigration as expected, and their cost benefits should be assessed in the future. At the same time, however, other employees and entrepreneurs moving to Finland do not have access to the fast track service as they have to go through a two-stage permit process, which is considerably slower. In 2022, the process of granting a work-based residence permit for an employee lasted for an average of ten weeks. For nurses and practical nurses, the permit process can last between five or six weeks and several months. Temporary abolition of labour market testing for a number of healthcare and social welfare professions in autumn 2021 has speeded up the permit process in the Uusimaa region.4

A family member of a person lawfully residing in Finland can only be granted a residence permit on the basis of family ties if the applicant’s livelihood in Finland has been secured. If, for example, there are two adults and two minor children in the family, the applicant must have a monthly net income of EUR 2,600. Even though the income limits are not absolute, they may pose a significant obstacle to foreigners in a number of professions. The need for information and authenticated documents and the oral interviews with the applicants in the Finnish diplomatic missions are the main reasons slowing down the application process for employees’ family members. It is stated in the audit that a more extensive outsourcing of the residence permit tasks of Finnish diplomatic missions, remote interviews with the applicants and certification of employers would also speed up the processes used by the applicants and employers and help applicants to save travel costs. Amendments to the Aliens Act that entered into force on 23 February 2023 provide a basis for introducing these measures.4

In the audit, these issues were examined, by way of example, from the perspective of the health and social services sector where, according to estimates, thousands of foreign employees would be needed each year. However, work-based immigration is hampered by the fact that persons who have obtained healthcare and social welfare qualifications outside the EU and the EEA must be granted the right to practise their profession by the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health (Valvira) before a work-based residence permit can be issued. Between 2018 and 2021, professional practice rights were granted to between 400 and 500 healthcare and social welfare professionals each year. To obtain the professional practice rights, the applicant must provide Valvira with sufficient proof of their language skills by submitting a language certificate. However, the employer is responsible for ensuring that the person in question has the language proficiency required for the task. Valvira may also require the applicant to complete compensatory measures or additional studies. A qualification path is available for persons trained as doctors and dentists, but nurses can only obtain the required qualifications by working in specific projects. However, no permanent funding has been allocated to the qualification training.4

Recommendations of the National Audit Office to promote work-based immigration

Advisory, guidance, integration and settling-in services for work-based immigrants should be strengthened and provided on a permanent basis in all parts of Finland.4

Gaps in the knowledge base of work-based immigration should be investigated and rectified so that the data describing the grounds for issuing a residence permit can be combined with other national register data.4

The proposals set out in the strategic roadmap 2022–2027 to finance, develop and establish qualification training for foreign employees prepared by the working group examining how to ensure the adequacy and availability of personnel in health and social services should be implemented.4

Training and coaching services provided by municipalities offer young people a path to working life

The purpose of the vocational education and training reform, which entered into force in 2018, was to make vocational education and training into a skills-based and customer-oriented system. The purpose of the follow-up on the audit of the preparation and implementation of the reform (2/2021) was to determine how educational offerings supporting employment have been promoted, how the commitment among employers to learning at workplaces has been surveyed and how the knowledge base behind funding decisions has been strengthened.5 Based on the follow-up, actions of the education administration have made vocational institutions better placed to provide training supporting employability. Allocation of funding is now on a slightly more efficient basis than in the past, and measures have been taken to make the contents of vocational qualifications more flexible. Measures have been taken to strengthen the knowledge base of the funding based on the effectiveness of vocational education and training by automating the collection of feedback from students and work counsellors and by preparing the use of the National Incomes Register in the production of information on the placement of graduates in work or education. The knowledge base of workplace commitment has also been improved, and a pilot on the benefits of training compensation is under way. Even though a great deal of progress has been achieved, providers of vocational education and training should continue to expand the service and training offerings arising from the needs of working life.5

In autumn 2022, in the final report on the project to develop cooperation and provider structure in upper secondary education, it was proposed that the appropriation for vocational education and training should be divided into two funding paths: funding for compulsory education and funding for continuous learning. Allocation of the appropriation would be decided on in the Budget each year. Division of the appropriation would strengthen basic funding for compulsory education and simplify the criteria for determining the funding for vocational education and training. Division of the funding would also provide prerequisites for updating the criteria for the funding for continuous learning so that better consideration would be given in them to the objectives of education and training intended for the working-age population and the needs of business operators. At the same time, it could also ensure the profitability of organising educational and training modules that are smaller than qualification units.

The purpose of the workshops, which are mainly organised by municipalities, is to use coaching to improve young people’s life management skills and capacity to access education and training, to successfully complete their education and training and after that to enter the open labour market or access any other service that they need. Based on the follow-up on the audit of youth workshops and outreach youth work, the purpose of the workshop activities and monitoring of the activities is to ensure that young people outside education, training and working life are able to participate in workshop activities intended for young people.5 A new type of cooperation with education and training providers was started in workshops after the act on the preparatory education for upper secondary qualifications entered into force in 2022. However, extending compulsory education to the age of 18 might have greater impact in the coming years than any individual measures as it can be assumed to increase the number of young people completing upper secondary education. It could not be unequivocally determined in the follow-up what improvements have been achieved in the allocation of outreach youth work grants to the municipalities that need them most. Correct allocation of the grants in accordance with service needs can be reliably estimated on the basis of statistics.6

Complex and fragmented nature of the service systems makes steering and management of the systems more difficult

Many of the public service systems and their administrative structures are complex and fragmented. The services are provided by a large number of actors in different administrative branches, some of them operating nationally and others operating on a regional or local basis. From the perspective of the service providers themselves, there is often ambiguity and overlap in their tasks and responsibilities, and this is also the view of many service users. A complex and fragmented service system is difficult to steer and manage. The objectives and tasks set for the system are difficult to implement, and the cooperation and sharing of information between the actors does not function properly. This has been the conclusion in several audits.4, 7-9

The complex nature of the public business service system has been known for many years to the parties responsible for managing the system. Measures have been taken to streamline the system; for example, services have been digitalised, service packages, paths and information systems have been built, and cooperation and sharing of information between service providers have been promoted. Based on the audit, improvements have been achieved but measures focusing on one part of the system or a single service do not solve the problems arising from the functioning and steerability of the system as a whole.7

Problems concerning the manageability of the business service system are also reflected in the fact that the service system is steered and developed on an actor-specific basis and there is little coordination at overall level. The audit revealed that based on short-term targets and performance-based indicators, it is not always possible to reach conclusions on the cost-effectiveness of the service system. Moreover, it is impossible to assess the economic efficiency and productivity of the service production because no information on the working time resources allocated to public business services is available. There are also problems concerning the availability of the shared customer-relationship management system of business service providers and the usability of the information. The National Audit Office recommends that the steering of the business service system and the division of labour between actors should be clarified and that the development of the operational indicators and information systems should continue.7

Digitalisation is also a key component in the national objectives for healthcare and social welfare, in which high priority is given to cooperation between wellbeing services counties, especially in the overhaul of client and patient information systems, and the development of healthcare and social welfare information production as a management tool.8 However, based on the audit, the link between monitoring of the achievement of the objectives and steering remains unclear. The national hybrid steering model for healthcare and social welfare currently under development combines instruments for normative, resource and information steering. It is recommended in the audit that a national vision should be drawn up to support the digitalisation of healthcare and social welfare and that concrete objectives and monitoring indicators should be prepared.8 The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health launched information management and digitalisation strategy work in healthcare and social welfare in cooperation with the wellbeing services counties in spring 2023. The purpose of the strategy work is to create common goals and development priorities for digitalisation and to agree on methods and measures and the division of tasks for the next ten years.

Based on the follow-up on the audit of the digitalisation of teaching and learning environments in general education, the responsibilities and tasks of digitalisation actors have not been changed after the audit in accordance with the National Audit Office’s recommendations.9 Measures have been taken to compile and update the steering and operating models for digitalisation in a comprehensive manner but the work has made only slow process. However, more progress has been achieved in the work to develop the architecture for digitalisation information management. In the view of the National Audit Office, the steering and development of the digitalisation of general education between ministries, government agencies and municipalities should be strengthened by means of structural, resource, information and evaluation-based steering, taking into account tangible and intangible resources.9

More attention should be paid to customer needs and regional special features in the development of public services

According to the audit findings, the availability of public business services and the provision of the services are generally at good level. However, there are regional differences in the provision of the services, and too often, services are provided from the perspective of the service providers.7 Especially in Uusimaa, the provision of public business services lags behind the needs. Furthermore, the TE services reform 2024 (380/2023), to be introduced at the start of 2025, is seen as a potential risk for the sharing of information, cooperation and system steering between business service system actors. If the coordination of the services becomes more difficult, there may be regional variation in their quality and content.7

Observations on the consideration of customer needs were also made in the audit of Suomi.fi e-services.10 As a rule, public administration organisations have an obligation to use Suomi.fi services, the purpose of which is to improve the availability and quality of public services and to boost the efficiency of public administration. Of the eight Suomi.fi service packages covered by the audit, three were extensively used in public administration at the time of the audit. As a whole, the service introduction processes are now running more smoothly than before, but there is not enough discussion on the service development needs with user organisations and there is little transparency in the setting of development priorities. It is recommended in the audit that the focus in the service development should be on essential needs and use cases that are ultimately reflected in the end users (citizens and companies). Strategic steering of Suomi.fi services should also be clarified, and more systematic and proactive development of services should be ensured by means of funding.10

The challenges arising from the digitalisation of the service system are also discussed in the audit of the healthcare and social welfare information systems.8 The starting points of the wellbeing services counties are different: in some of them, information systems have already been harmonised whereas in others, information systems are fragmented. The situation in the transition phase has been closely monitored, and a roadmap for the period 2021–2023 was prepared to support the implementation of the reform. The implementation of the key ICT preparation tasks is part of the roadmap. The wellbeing services counties have been grouped into five collaborative areas, which are tasked with regional coordination, cooperation and development in healthcare and social welfare. The aim is to harmonise all key information systems (especially client and patient information systems) at the level of collaborative areas. In the view of the wellbeing services counties, adequate steering has been provided during the transition phase but not enough consideration has been given to the differences between wellbeing services counties. Based on the audit, nationwide ICT steering has not sufficiently encouraged counties to cooperate with each other, and cooperation between collaborative areas should be more strongly supported. Information system cooperation between the counties is also carried out through inhouse companies, such as DigiFinland. It is recommended in the audit that the national digital services in healthcare and social welfare should be coordinated in accordance with the counties’ needs.8

Recommendations of the National Audit Office for improving the service systems

The overall management of the public service systems, such as health and social services, business services and education and training services, should be improved by specifying the division of labour between organisations operating within the systems and by clarifying and harmonising normative, resource and information steering.7–10

Services and their digitalisation should be developed systematically and in a proactive manner. This requires that essential customer needs and regional characteristics are identified and taken into account and that a stable funding base is ensured.7–10

The chapter is based on the following audits and follow-ups:

Follow-up report of 27 April 2023 on the audit Reform of vocational education (2/2021) (in Finnish)

Effectiveness of the public business service system (5/2023)

Funding and steering of the digitalization of healthcare and social welfare (9/2023)

Current status and development of the Suomi.fi services (10/2022)